This post is part of our new "Getting Accepted" series, a guide to prepping portfolios and getting into the best design programs across the United States. For our first edition, we're focusing in on The University of Pennsylvania's Integrated Product Design graduate program, which has an upcoming application deadline for their 2021 program on February 1, 2021.

UPenn's Integrated Product Design Program (IPD) began in 2007 with the idea that designers' work thrives in an interdisciplinary environment. "There is this fundamental belief that in order to design well, you need to understand more than design," says Sarah Rottenberg, Executive Director of the IPD Program. "You need to really understand the business side of things, the engineering side of things as well as the design side so that you have more control over the ability to implement and execute your ideas." One of the IPD program's core strengths lies in its relationships with the Ivy League university's Weitzman School of Design, School of Engineering, and the Wharton School of Business. IPD students take courses within each of these school as a way to control and customize their own education to their liking. "As an example, we get students who are interested in healthcare design, and there are healthcare classes they can take in Wharton," Rottenberg notes. "And there's an Architecture of Health class in the School of Design. There's a Rehab Engineering and Design class in engineering. So they can kind of personalize the degree to address the things they're interested in."

So who is this program for? The type of student who understands the benefit of knowledge in multiple fields with a clear idea of their direction for the future. Whether the idea is to become the founder of a company, or eventually a director within a small consultancy, IPD's goal is to get you ready to roll with any punches the future may throw you.

We recently chatted with Rottenberg to hear more about what it takes to get into IPD's small, prestigious program and what students can expect to get out of their two years there.

Core77: What kind of industries do your students often go into?

Sarah Rottenberg: One thing that surprised and delighted me this year was our students were still getting hired even in the middle of a global pandemic. Once April hit [I worried], but they are getting super interesting jobs. There are always a portion of our students who start their own companies right after graduating, and typically they are pursuing ideas that they developed in school, sometimes they've gotten some funding from various entities within and outside of Penn. So founder or co-founder is definitely one pathway, but it's not the biggest pathway. Students go to work for design consultancies in a variety of roles. Sometimes it's design strategist, design researcher, product designer, design engineer, because they come in with different backgrounds. They go to work in-house for big and large, big and small corporations. There are a lot of paths.

I was just texting with an alumni who works for Tushy, they make bidets. We now have four IPD alumni who are working there, which is great and they love that company. I think that small startups like that value the skills of IPD students because they can wear multiple hats. And then in larger companies, you know, students who want to take a more specific, concrete role can really thrive. We have a number of students, for example, in various engineering roles at Apple right now. So it's pretty varied and diverse.

How would you define what makes for a successful IPD grad student, and what do students who get in need to do to excel in the program?

I think a successful student has a good balance between drive and open mindedness. You get out of grad school what you put into it, so being willing to put your all into it is really important. Students who are tackling hard courses, stretching themselves and participating in extracurricular activities [do very well]. We have a really active graduate association, a group of students who do programming for the students, so engaging with that for example. And students who take responsibility for helping to create their own experience and the experience of others, I think really thrive in the program. We've been around long enough that we have a strong culture. So I think that the idea of being excited about everything Penn has to offer and taking advantage of it, also being excited about taking a little bit of responsibility for creating your own experience and a great experience for others are two things that really make for a good experience.

UPenn's brand new Tangen Hall facility includes incubator spaces and maker spaces to pilot student-led ventures, a test kitchen for food-centric startups, and the Integrated Product Design Program.

UPenn's brand new Tangen Hall facility includes incubator spaces and maker spaces to pilot student-led ventures, a test kitchen for food-centric startups, and the Integrated Product Design Program.

I was curious if you could expand on what the typical backgrounds of IPD students are and what they're interested in.

We try to create a deliberately diverse cohort from a number of different perspectives, one being academic background. We take students from design, engineering and business backgrounds. It tends to be 40% design / 40% engineering / 20% business; that is not a hard and fast rule where we're slotting people, but that tends to be kind of what we shoot for.

We have diversity from an age perspective. Some are just out of school, we don't require that they've worked, but some have worked for 10 or 15 years and we like to have that spectrum. The majority are in this sweet spot of probably two or three years out of school. We look for diversity of country of origin. The program is predominantly students from the US, but within the US we try to get diverse representation, and then we have students in the program right now from Norway, Argentina, Ecuador, Peru, China, India, Korea, the Philippines. The students learn so much from each other. The more diversity we can introduce, the more different perspectives and life experiences we can have, the better.

They need to be strong students and have strong academics because it's an Ivy League University—the standards are high, the work is hard. But we also want students who show creativity and quirky perspectives on the world. So I'm always looking for, what's your interesting take? I look for that in essays and portfolios. We know students are here to learn, so we don't expect them to know everything, but we expect them to have a strong background in one of the three fields—design, engineering or business—and to be able to show an aptitude for the others. Sometimes that's an engineer who minored in entrepreneurship, or somebody who went to school for engineering and then worked in finance for two years, or a designer who co-founded a company. And again, because they learn so much from each other, we're interested in what kind of stuff they have done outside of school, extracurricular engagement, we're looking for evidence of people who are likely to be really engaged in the community. For example, we love Peace Corps workers and people who were RAs in their dorms, things like that.

What types of skills should accepted students expect to come in with in order to excel? And what will they learn that they might not know already?

It's pretty varied because they come in from different disciplines. We do have some required Foundation classes. So if you have a background in industrial design and you've never taken an engineering or business class, you will likely be required to take an engineering Foundation, which is an intensive summer class, and a business Foundation, which happens your first or second semester in the program. And it's the same for every class, so they should have the skills associated with their discipline, but we don't necessarily expect everyone to be even adept at something like Adobe Suite. When we look at portfolios, we really look differently at a portfolio from someone with a business background and someone with a design background. There isn't one set of skills required, but we want to see curiosity. We want to see, are they passionate about the work that they've done? Do they care about people? Because that's sort of a core underlying theme of the program is designing things that matter to people. So it's more about mindsets, I would say, than skills that we're looking for.

To any prospective student looking to apply next year, what should they be doing right now to prepare their applications and portfolios? And what kind of projects do you want to see from an applicant?

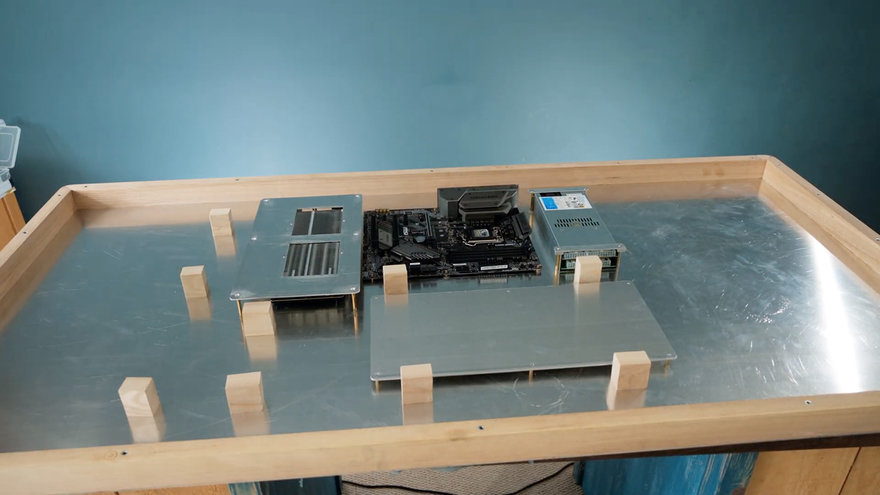

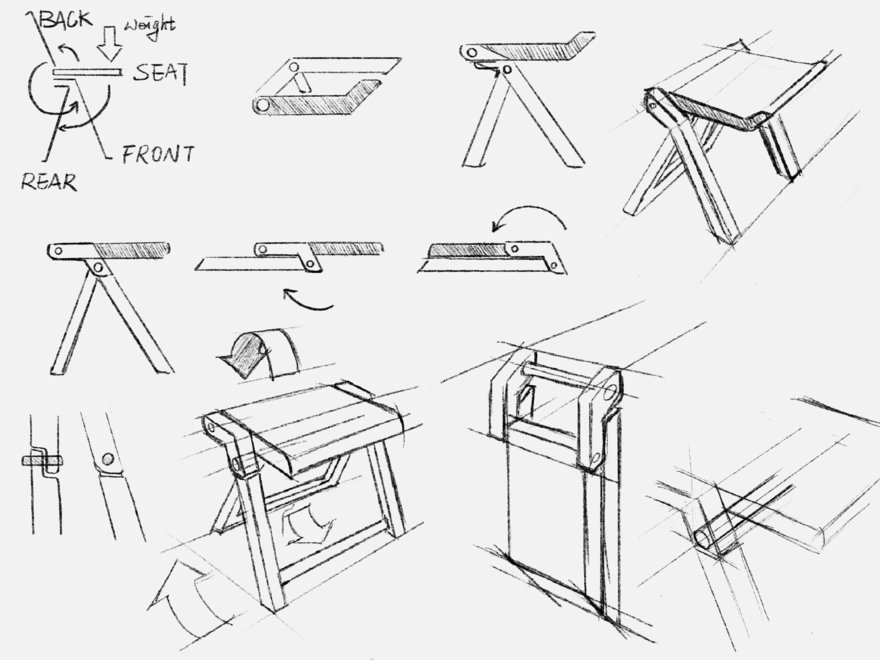

We like to see a mix ideally of academic and no- academic projects. Even if someone doesn't have a ton of work experience, show us stuff from internships, or even hobbies. Visual Communication and storytelling is something we really work with all of our students on. And they do come in at different levels, but the better they are at telling a story in their portfolio, the better their chances of showing us who they are. So start by looking at a wide variety of portfolios that are available online, I would look at IPD alumni's current portfolios. Think about what projects you have or what stories you can tell us through your portfolios in terms of, you know, taking work from a class project and turning that into a concrete story. Or sometimes it's something like building a desk, I'm sure people are building desks for themselves as they're working from home. I bet we'll see a lot of those! So it can also be hobbies and personal projects, those are very interesting to us.

Then in the personal statement, one of the things we're really looking for is, are you going to be a fit with us and our community? Can we offer you what you want to get forward to the next level? Are you going to be happy at Penn, are you going to get what you want out of the program? I think doing research into the program, the culture, or reaching out to me or current students or alumni is also really important so that they can have that sense of fit and whether it's right or not.

What sort of qualities are you seeking in an IPD applicant?

I want them to be collaborative. I want them to be curious. I want them to be doers, and experimenters and tinkerers. I want them to care about people, care about who they're designing for and what they're making. And I want them to care about what positive impact they can have on the world through the things they make in the program and beyond. I think that's my ideal candidate.

What does it take to get in? And are there any examples of applicants who came close but missed the cut? And if so, what were the deciding factors? And obviously, this can be vague.

Again, I think it goes back to fit. Students should do their research and understand what the programs are. Not everyone knows exactly what they want to do when they graduate from the program, and in fact, I would say that of the people who think they know exactly what they want to do when they graduate, 90% of them change that while they're in school. Which is fine! But I think really being conscious of who they are and what they hope to get out of the program helps.

I think sometimes people don't tell their stories very well. We actually had a student who was waitlisted and then he got in, and after a year in the program, he said, "Oh, I realize now that if I had just structured my portfolio differently, I probably would have gotten the first round." I think the more that they can really tell the story of who they are, what they're capable of and what they want to do, if they don't get into Penn it might be because Penn is not the right place for them and they will get in somewhere that is the right place for them.

"Jarvis" is a mixed reality headset for diagnosing ADHD in children designed by IPD students Parker Murray, Varun Sanghvi and Michael Yates.

"Jarvis" is a mixed reality headset for diagnosing ADHD in children designed by IPD students Parker Murray, Varun Sanghvi and Michael Yates.

What differentiates an application that is satisfactory from one that's exceptional?

There are so many ways for people to learn how to do a human centered design process. A lot of people can show you how they've gone through these steps. But not a lot of people can show you, 'this is the insight I gathered based on step A, that led me to solution B.' And I think that's the thing, whether that's about a penetrating insight about people's needs or about something you learned in an experiment that you are doing with a technology that drove you to make a different choice. It's not always insights about human behavior, but being able to really be articulate about your thought process and learning from what you do and then changing what you do next. I think that is unusual to see in a portfolio and when we see that we are always thrilled, because that tells us a lot.

I would say the other thing is, I like to see stories about projects where people peeked into corners of the world that maybe I didn't even know existed, explore them deeply and create something in them. For example, there was an engineering student who did a senior design project where she was designing for students at a school for blind children, and showed a lot of like, "I created this and then I prototyped and tested that." The unusual projects, where someone really dug into a topic and made a lot of progress, I think is always compelling.

But don't feel like you have to go out and design for blind children, right? There are a lot of great ways to show interesting [work]. You see the same projects over and over because design schools only have like a certain number of topics explored and identified. But then you see a solution to that problem that you've never seen before. That's always delightful. So surprise us in some way with the work that you do.

Any last thoughts you'd like to share about the program or the application process?

I think it's super interesting right now how design is changing. The way people understand design is changing, the way people practice design in the industry and in different kinds of businesses is changing. I think schools are also changing pretty quickly. Something that students should do when applying for schools is look at the programs where you have the ability to explore those changing dynamics and be on the edge of it. [Design] is just going to be a rapidly evolving field as technologies change, as commerce changes, so we always kind of have to be able to understand the implications of those changes and keep up with them.

[At UPenn] I think we teach students how to learn new things, and how to learn things that are maybe outside of their comfort zones because of this interdisciplinary nature that helps them keep up as things continue to evolve. So I think that is one of the more important things we teach is just how to keep learning and keep integrating new things into your process.

UPenn's IPD Graduate Program is now accepting applications for 2021, with an application deadline of February 1, 2021. Take what you've learned here to finish your IPD application! Apply now at ipd.me.upenn.edu/admissions/.

from Core77 https://ift.tt/3gUOC3X

via

IFTTT

Image credit:

Image credit:

"You're getting the silent treatment until I GET MY SHARK BACK"

"You're getting the silent treatment until I GET MY SHARK BACK"

"I don't see why it bothers you so much. If I place the bolster between us, I can rest my arm on it and more easily see my wristwatch. This is not about me being distant."

"I don't see why it bothers you so much. If I place the bolster between us, I can rest my arm on it and more easily see my wristwatch. This is not about me being distant."

UPenn's brand new Tangen Hall facility includes incubator spaces and maker spaces to pilot student-led ventures, a test kitchen for food-centric startups, and the

UPenn's brand new Tangen Hall facility includes incubator spaces and maker spaces to pilot student-led ventures, a test kitchen for food-centric startups, and the

"Jarvis" is a mixed reality headset for diagnosing ADHD in children designed by IPD students Parker Murray, Varun Sanghvi and Michael Yates.

"Jarvis" is a mixed reality headset for diagnosing ADHD in children designed by IPD students Parker Murray, Varun Sanghvi and Michael Yates.

"2 containers with living hinge connections; the left one is shown in the correct print orientation resulting in a stronger hinge while the right container is in the incorrect orientation relative to the print bed"

"2 containers with living hinge connections; the left one is shown in the correct print orientation resulting in a stronger hinge while the right container is in the incorrect orientation relative to the print bed" "The living hinge should be printed in a single strand of thermoplastic to improve strength"

"The living hinge should be printed in a single strand of thermoplastic to improve strength" "Recommended dimensions for a living hinge designed for injection molding"

"Recommended dimensions for a living hinge designed for injection molding" "Dimensions for successfully printed FDM living hinge. Dimensions will vary by technology (see below for recommended dimensions by technology)"

"Dimensions for successfully printed FDM living hinge. Dimensions will vary by technology (see below for recommended dimensions by technology)"