If your kid's learning to ride a bike, you'll add training wheels. But one of the smartest "hacks" I ever saw was in Japan in the '90s, where a clever father removed the pedals on his kid's bike. The kid sat on the bike and went up and down the street, Fred-Flintstone-style, using his feet to move forward. After 20 minutes, the father put the pedals back on. The kid then pedaled away--very wobbly and halting, but he did not fall over. His body had already grasped how to balance by hoofing around on the bike. And the father didn't have to buy training wheels.*

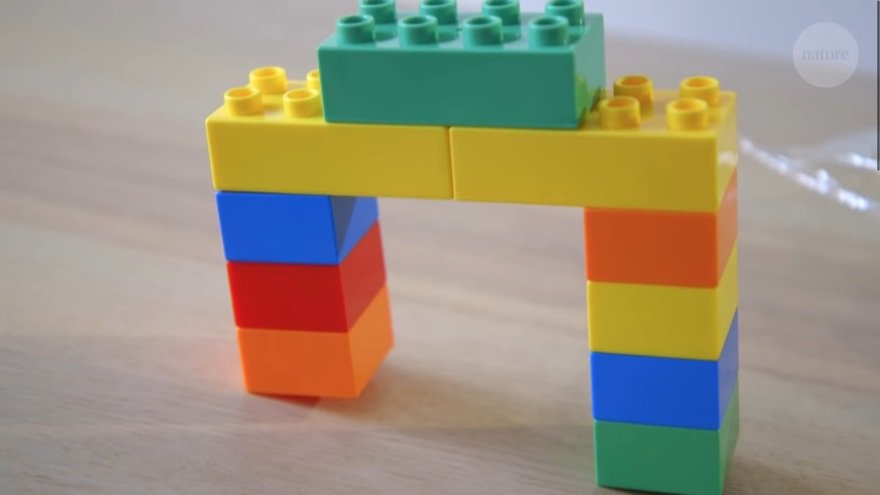

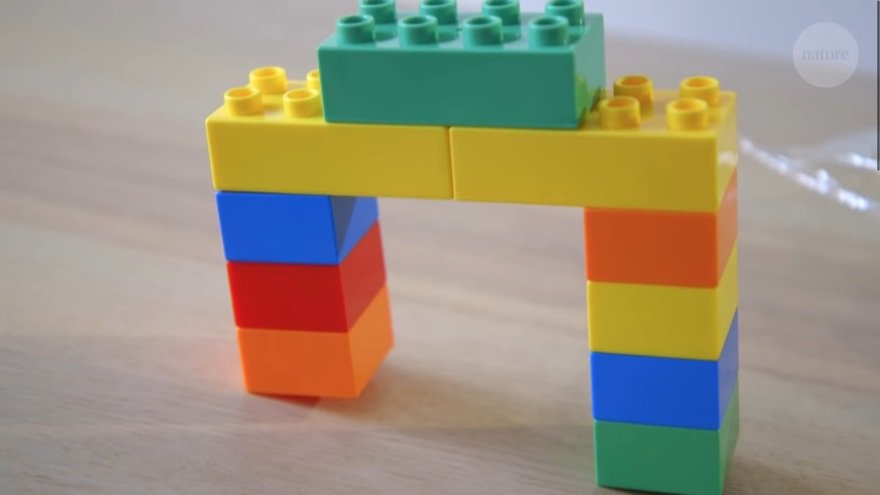

Look at this LEGO construction, below. It won't stand straight. How would you fix it in one move?

Chances are your instinct was to add a brick to the left side. It occurs to far less people to remove a brick from the right side.

Why? Leidy Klotz, a University of Virginia engineer and architecture professor who "studies the science of design," was playing with LEGOs with his son when he experienced the example above. "I reached behind me to grab a block to add to the shorter tower. As I turned back toward the soon-to-be bridge, three-year-old Ezra was removing a block from the taller tower. My impulse had been to add to the short support, and in that moment, I realized it was wrong: taking away from the tall support was a faster and more efficient way to create a level bridge."

Klotz brought the LEGO test to Dr. Gabrielle Adams, a fellow UVA professor who teaches experimental design. She, too, instinctively added a block to the shorter tower. Klotz told her Ezra's solution.

"Oh," Dr. Adams said. "So, you're wondering whether we neglect subtraction as a way to change things?" A study, "People systematically overlook subtractive changes," was born.

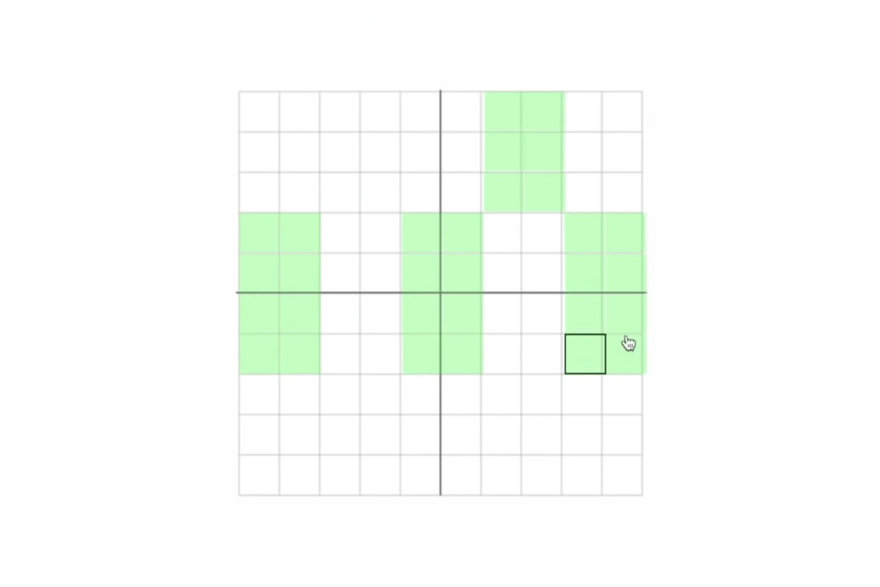

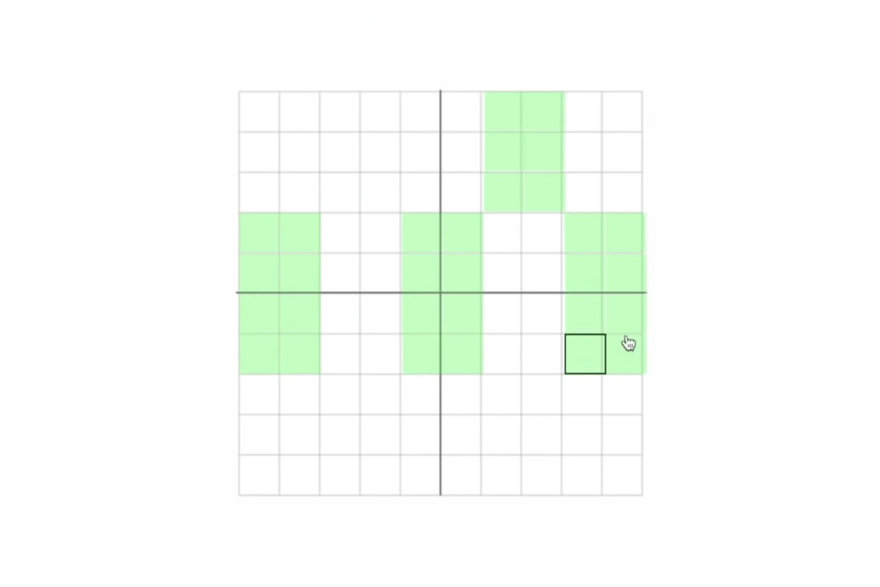

Klotz and Dr. Adams worked with psychology professor Ben Converse and postdoctoral student Andy Hales to design eight experiments where test subjects could choose to add or subtract elements to a variety of tasks. As one example, they were shown this pattern on a grid, where they can add or remove green squares. They were asked to make the pattern symmetrical.

78% of participants did it by adding green squares to the left rather than subtracting from the right.

Participants were asked to improve an essay they had written. 80% added text, rather than subtracting.

In this modification of the LEGO test, participants were asked to "improve" the design, with the only stipulation being that the figure must still be able to fit beneath the roof:

The majority added more supports to the roof, rather than simply removing the one block that prevents the roof from sitting flush.

"We asked research participants to make changes to designs, essays, recipes, itineraries, structures and even miniature-golf holes," the researches write. "Our studies show that people's first instinct is to change things by adding. When they are able and willing to think a little longer, they are perfectly capable of finding subtractive changes. But they usually don't think longer. They quickly identify an additive idea that is good enough, put it into action and move on."

The researchers found that simply reminding the participants that subtraction was an option, increased the chances that they'd use a subtractive solution. They also found that distracting subjects during an experiment--increasing their "cognitive load" by requiring them to simultaneously check a sequence of numbers scrolling across a screen--led them towards additive solutions, which appears to be our natural cognitive bias.

Think of those scrolling numbers as an avalanche of e-mails

Think of those scrolling numbers as an avalanche of e-mails

So, if you're a design manager and you'd like to see more pared-down designs from your team: Remind them that less is more. Don't distract them with managerial B.S. when they're getting in the zone. And if you can afford to relieve them of even a little time pressure (I know, fat chance), do it.

Klotz, by the way, subsequently wrote a book on the subject: "Subtract - The Untapped Science of Less."

"Whether we're building Lego models or cities, grilled-cheese sandwiches or strategic plans, our minds tend to add before taking away. Even when we do think of it, subtraction can be harder to pull off because an array of biological, cultural, and economic forces push us towards more. But we have a choice—our blind spot need not go on taking its toll on our cities, our institutions, and our minds. By diagnosing our neglect of subtraction, we can treat it."

_________________

*Sadly, I've learned that the remove-the-pedals trick was commercialized by an American inventor in 2007 into a bicycle manufactured without pedals. It's even cited in the researcher's work. But rather than purchase a no-pedals bike that becomes worthless to the child once they've mastered balance, I think temporarily removing the pedals of an existing bicycle is far less wasteful in the long run. So ironically, this no-pedals bike is actually an example of additive thinking.

from Core77 https://ift.tt/2Qfsv11

via

IFTTT

How the big dogs do it

How the big dogs do it An Arrival Microfactory

An Arrival Microfactory

Think of those scrolling numbers as an avalanche of e-mails

Think of those scrolling numbers as an avalanche of e-mails

Last generation, left. New one, right.

Last generation, left. New one, right.

Image: tomislav medak - München : Butterfly Stool by Sori Yanagi,

Image: tomislav medak - München : Butterfly Stool by Sori Yanagi,